Progarchives.com has always (since 2002) relied on banners ads to cover web hosting fees and all.

Please consider supporting us by giving monthly PayPal donations and help keep PA fast-loading and ad-free forever.

/PAlogo_v2.gif) |

|

Post Reply

|

| Author | |

toroddfuglesteg

Forum Senior Member

Retired Joined: March 04 2008 Location: Retirement Home Status: Offline Points: 3658 |

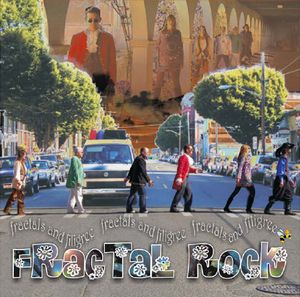

Topic: Fractal Rock Topic: Fractal RockPosted: January 08 2011 at 11:54 |

|

Based in Silverdale, Washington US outfit Fractal Rock was initially formed by Joel Martin, Dave Hawkins and Robert Westcott, and as time went by Kristine Tibbs, Deena Lien-Richards and Dave Turissini would join. They started recording their debut album in 2009, and in the summer of 2010 Fractal Rock self-released their debut effort Fractals and Filigree. The band have chosen to let anyone interested download the digital version of the album for free, and their philosophy seems to be to get better known rather than to rigidly pursue the financial aspect of being a recording artist. At least for the time being. I downloaded their free album and got in touch with the band for their story. ######################################

ProgArchives features your band’s

biography, but since we’ve the pleasure of having you here, give us

the skinny. Why the name Fractal Rock? And

why—with all the choices out there—do you play this kind of

music?

Joel

Martin (keyboard & engineer):

Well, our bio has changed a little. Julando Samson was set to play

with us but ended up needing to go in a different direction. Those

kinds of changes are the toughest for any band, because on top of

needed skill (if not talent), there has to be a chemistry between the

players: artistically, psychologically, philosophically, and, of

course, musically. (A

voice from the back calls out: “Don’t forget SEXUALLY!”)

Then we landed a new lead guitarist, Jeff Wittekind, a very talented

man, B.A. in music, sight reads, plays in several jazz bands, just a

real boon to all of us. Other than that, I’d say we’re basically

the same people … you know, except for us being completely

different, older, and yeah, dare I say it, smarter, wiser, and right

now, at the top of our game as artists and musicians. (A

voice from the back calls out: “And SEXUALLY!”)

As

for the band’s name, ‘Fractal’ represents the inherent

diversity that lies around the edges of music, while recognizing the

same thing that Leibniz, Riemann, Mozart, Keppler, Beethoven,

Einstein and others perceived, that underlying the universe, and all

that lies within—including music—there’s a symmetry, an order …

there is math!

But

what about where there doesn’t seem to be symmetry? Where things

are rough, appear unnatural … are out of place, live on the edge?

Turns

out there’s order there, too. And it can be demonstrated,

expressed … in the form of fractals, rough or fragmented shapes

that are reduced-sized copies of the whole. Think of it as there

being a pattern beneath seeming chaos. With our music, in part,

that’s what we do. Like Mozart, or perhaps like Mozart dropping

acid, we work on variations of a theme. The thing is, our variations

aren’t just alterations of notes or musical progression, but rather

entire soundscapes. (A

voice calls out from the back: “Sexsca—!” Shuddup,

Joel yells.)

Some might say ‘sexscapes.’

Some

people get caught up on concept albums, but why? First, though

there’s been some good ones, for the most part, they’re pretty

dated. And second, let’s get real. If Picasso’s stuff all

looked the same, none of us would ever have heard of him.

With

art, there are basically two paths, one involves making money, such

as with jingles, commercial art, ad-work, etc, the other’s about

expression. It’s the rare goose that marries both. But that, of

course, is our goal. We aren’t averse to making some coin, but at

the same time, we want the freedom to express ourselves as arteeests.

Progressive and experimental rock, acid rock, etc., not having many

boundaries, offers this kind of freedom. Plus, it’s fun to tinker

with—to find the fractals that yearn to be expressed. And people

who’ve caught the taste for it, don’t mind the experimentation.

With

myself, I happen to like free jazz, a form which many can’t seem to

stand more than a coupla minutes. With the rest of the band, though,

we work more of a crossover so as to broaden the audience. Prog’s

the nexus where we can not only blend our varied musical interests,

but where we can also shamelessly lift from the greats: Mozart, Bach,

Liszt and the rest, and then shred their work. (A voice calls out

from the back: “Shred ’em into FRACTALS!”)

Dave Turissini (bass guitarist):

The name was chosen before my being part of the band, but I was fine

with the handle. What drew me to the group was the fusion of

classical themes with rock instrumentation. I’ve always liked

music that was a sensory experience, that, you know, kept the

listener a bit off-balance and did the unexpected.

With the style, well, I wanted the

challenge. Most of my life I’ve been playing top-40 and mainstream

pop. But in my heart, I’ve always been a what-if man.

A what-if man?

Bill Bruford (William Scott Bruford,

original drummer for Yes) was recently

quoted as saying, “I’ve always been the guy to ask: ‘What if we

play this in 5/4 instead of 4/4?’ Or, ‘What happens if we play

this chord progression backwards?’”

And that’s it, being a what-if

as an artist; that’s the heart of all art.

What do you mean?

Easy. Without that central question,

there’d never be anything new or different. How’d

you come to be in the band?

Kristine

Tibbs (vocalist and lyricist and band-hottie):

Truth is, Joel heard me sing a couple Christmas songs and asked me

if I had ever considered singingprogressive

rock. My response? “Uh, no.” Then, shocking me further, he

handed me some music and told me to write the lyrics. “Yeah,

right,” I said. But I went for it.

At first I was overwhelmed. There wasn’t any way in Hell I could come up with melodies, let alone putting down some words, but I persevered, till one day, outta the blue, the lines started to come, flowed even, and I’ve been working ever since. And I discovered something. See,

as a kid, I hated acid rock. And, really, I suppose I could say that

I still do. But such a line is akin to a person saying that they

don’t like food. Well, there’s a lot of different kinds of food

out there, isn’t there? Coming together with these particular

noiseicians, I’ve found a niche I can grind with.

Dave Hawkins (guitarist): For

myself, I love alternative/progressive-type music: for me that is:

King Crimson, Adrian Belew, Porcupine Tree, as long as

it’s different than the main stream (with due nods to Led

Zeppelin, Jimi Hendrix, and a lot from the ’60s and ’70s).

Coming from the psychedelic era (and perhaps never leaving it), I’m

not shy around any form of good music (especially new sounds and

progressions), regardless of genre or type, but cringe at the thought

of anything that’s cookie cutter, dressed, or assembly-line

stamped. There’s groups out there, like boy bands, and single

artists, too, often female, that are nothing more than Santa Claus

performers … entertainers whose entire shtick was birthed out of

some white-board plan out of an executive meeting, with everything

derivative, fluff, glammed, and worse (if there is a cardinal sin in

music, this has got to be it), artificial.

Robert Westcott (drummer):

Fractal Rock ... it’s all about fractals, right? Like a

portion of something that’s from a whole, yet standing different or

unique. Each instrument … ever layer of sound is a

unique fractal of each song. Then, at the end, they bond

together in an artistic web that expresses a piece (a fractal) of

our souls. A piece of the whole. The same, yet

unique ... just like everyone around us.

… and what is your musical

background?

Joel:

Four or five I started learning piano, and was able to read music

fairly well by the time I was six. Introverted, and hitting the

first grade a bit on the young side, I found solace with the 88’s,

and began receiving training to develop my ear, and in short order,

could pick out tunes without any sheet music. By the second grade, I

was writing simple tunes—mostly two-note left hand, and three-note

right—and, by happenstance, learned to listen for moving tones,

drop roots, and counter harmonies. Age nine, I joined the school

orchestra, and continued in school bands well beyond high school,

while partaking of college-level music courses whenever the

opportunity came up. To date, I’ve been playing the bassoon for

36-years, bass for 33, piano for 43, and the drums for almost as

long. Do I consider myself a brilliant player? (Joel

smiles.) No,

just a great experimenter and appreciator (the latter meaning I have

an almost supernatural ability to detect musical sh*te), which helps

me to connect—as an engineer and a musician—with my fellow

players.

I

do, though, have an opinion that it takes three things for a person

to succeed as a serious artist/craftsman. One, they have to be able

to read and write music. With all due respect to garage musicians

who solely know how to play, the reality is the serious artist must

be able to pen down their music in such a way that it can be

recreated later, by themselves and/or others. Two, a person must

have a sound understanding of music theory; and three, know how to

use a metronome.

Kris:

I’ve been singing my whole life, classical and Broadway. Give me a

Broadway song, and I’ll belt it with the best of ’em. Rock’s

the new beast on the block.

Dave Hawkins: Started drumming

shortly after learning how to pee, and the guitar off and on for

almost as long, but when I decided to write, I chose to focus on

guitar work, and did—for at least the past 12-years. And though

I’m not as versatile as some (we all have our gods), and have no

plans to stop improving, I’ve found a place now to call my own.

One of the things—a strong-suit, really, dare I say?—I find

intriguing (and beneficial), is playing the guitar while keeping the

drums in mind, in terms of rhythm and syncopation. After all, if no

man’s an island, neither is an instrument! This has been not only

an aid with my own writing, but also when I get to play with others,

especially with such an inventive drummer as Robert (Westcott).

Robert: Thanks to my older

brother, been playing drums since high school (even got to record our

class’s graduating song), back in 1986. I learned a few cover

tunes over the years but never got into a cover band. Instead,

I’ve always had the pleasure of being involved with projects

dealing with original music. Every musician, if not every artist

period, despite the medium, starts, to one degree or another, by

mimicking a great. And why not? Gotta have a base to project from.

But then, a person’s gotta find themselves. And in the course of

things, what they need to focus their heart and soul into—their

passion. Of a truth, they have to put such things on the line, even

make themselves vulnerable in the pursuit of their craft. Working

with original music is a must-do to have that happen.

After high school, I joined the Navy,

and while serving, played with an original band for a couple of

years. Navy-time done, I auditioned for Nyxie, a great

project that introduced me to Julando Samson, a very unique

guitarist, and one whom I’ve had the pleasure of recording numerous

drum tracks for. Since ’05, I’ve also been part of a drum-line

called Pacific Alliance (where I really learned how different being

part of a drum corps is to being a kit player).  Please give us your long or brief

thoughts on your debut album Fractals And Filigree

released this year.

Joel:

Let’s get geeky. It was a bitch to engineer and mix … the drum

set alone had 16-mics, with some of the songs having in excess of

40-tracks. Hell, Cyclone

has about 54! That’s a lot of mixing. Thank God for the producer

version of Sonar 8.0. Plus, know that everything we did was

mixed-on-the-fly, meaning there was no destructive editing. To pull

that off, ya gotta have some serious computing power. In our case,

we used a top-line quad core with a raid, along with two dual cores.

We spent 840-ear-wreckin’-hours in the studio producing this

holy-of-holies. When all was done, I was wiped—and smiling. We

all were. There’s been some detractors (there always are),

bitching that the work’s ‘too artsy,’ but that’s been fine.

We understand what that means. Code-talk for ‘they’ couldn’t

have done it. For us … well, we love the work, are proud …

and’re putting it out there for FREE! For two reasons. One, to

gift our fans, and all the soon-to-bes, and as a big

you’re-number-one to all the neck-waggers who didn’t think we

could pull it off.

Dave

Turissini: The

album was a lot of fun to do, and with the entire project, I was just

amazed at how it drew from all across the musical spectrum, was just

an absolute panoply of instrumentation, style … hell, just about

everything but country, one total eclectic feast.

When

asked about it, I usually respond with: Imagine what would happen if

Frank Zappa would’ve somehow gotten into Modest Mussorgsky’s

(Mussorgsky: a

Russian composer and musical innovator in the 1800’s)

brain—while having access to lots of keyboards!

Another

way to look at it might be as a mashing together of Gentle

Giant, Yezda Urfa, and Tony

Orlando and Dawn.

Kris:

Personally, I’m in the company of geniuses. Joel is the most

artistically analytical person Ihave

ever met. A Mozart living in our century. Dave Hawkins is amazing.

He doesn’t play the guitar, he paints soundscapes with it.

Honest, there’s a little

genius in all my bandmates. Deena adds a whole different

dimension to the songs....

I love the music. It’s a lot of fun and has opened my mind to so much creativity ... it’s liberating. Dave Hawkins: Fractals and

Filigree exposed my strengths and weaknesses, and gave me the

first real Jack Nicholson moment I’ve had in a long time. It made

me want to become a better player—and by the end of it all, I had.

Robert: We wanted to highlight

our diversity, and connect with both the average listener as well as

with fans of the more complex, and we pulled it off, filling up every

ounce of space on the CD with 17 songs.

And the feedback’s been phenomenal.

Some have compared us to Yes, which is a helluva compliment,

and I can hear why. The extreme classical and prog rock influence is

there, similar to Yes, but without their brand of complex

vocal layers. Then again, there’s stuff that brings to mind TSO.

Everybody’s influenced by something. But in the end, who do we

sound like? Fractal Rock! We’re unique, and that’s a big

positive in anyone’s book. We’re not looking to fit a mold; with

Fractals And Filigree, we made our own, physically and

mentally pouring in everything we had, and then we broke it, and

that’s the paradigm we’re going to follow, each and every

time—(he smiles) the next project’s already rolling out.

Describe your writing … your

creative process?

Deena Lien-Richards (lyricist,

percussionist, and band’s fashion-guru): A very tough question.

Let me quote what Stephen King has to say about writing in his

book/memoir On Writing: “Fiction writers (sub in here

the term songwriters), present company included, don’t understand

very much about what they do—not why it works when it’s good, not

why it doesn’t when it’s bad.” I agree with King’s words.

The process is dynamic, fluid, and completely unpredictable.

Sometimes the mojo’s just there, and the work’s simple, and with

other songs, a person would rather get a colonoscopy done by a bunch

of rabid gondoliers.

The basic approach I take, however, is

probably the same as many, that of looking at the song’s title,

seeing or ‘hearing’ or, even better, feeling what the

message might be … and, of course, listening to the song (if it’s

already been more-or-less finished) to see if the title even fits or

might in-and-of itself be a speed bump to whatever message needs to

get married to the music. Other occasions, I take mental bus trips,

tours, if you please, back through my life experience, and then just

believe for the muse to hit. And yes, there’s also dreams—waking

and sleeping—that can be harnessed for good story/song/and sonnet.

The lyrics to “Gossamer Thread” came from a dream where I was a

spider living in a medieval castle, now how crazy is that? One of

the biggest keys of the whole business is: WRITE EVERYTHING DOWN.

Nothing’s worse than having some lines, a rhyme, a turn of phrase

that’s just spot-on, and then one forgets … didn’t have that

notepad handy on the side of the bed when they woke up at 3:00 A.M.

Things, words, melodies can hit anytime, anywhere, and under any

circumstance. The artist needs to make sure they can take it down

and file it away. You never know when it might come in handy.

Joel:

There is no one way. But often, the launching pad’s some fragment

I’ve put together, or from Dave Hawkins. Afterward, we see how it

might be woven or morphed with something classical. Dave and I both

religiously listen to a lot of great stuff, too many to list now, but

certainly the historicals: Listz, Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, the rest,

and then the modern classicals: Yes, Gentle Giant,

Hendrix, King Crimson, Zepp, Uriah Heep,

as well as other great hippie-esque musicians. Then, once Dave and I

have some kind of base structure, we turn it over to our bass and

drummer and they set in their teeth (and, man, are they sharp). When

they get done, the rough mix gets moved to our vocalists. There, the

melodies and lyrics get put into place and massaged, and when that

doesn’t work, they start to amputate and graft. When there’s an

opportunity, I’ll hash out part of a melody, typically because it’s

a natural part of some classical progression. There’s only been a

coupla times we’ve changed musical structure to accommodate lyrics,

and even then all we did was add a chorus, or extend a couple of

measures. The idea, of course, is not to come up with something

boring. We don’t write music for lyrics, or vice versa. By the

time any particular piece is close to done, the goal’s been to have

an interwoven work that’s seamless, and self-reinforcing, meaning

that every part’s a part, but collectively … well, we want what

every music-addict desires: Something that transcends.

Kris:

To sound as if I’m honoring the ’60’s (which was for music,

like the industrial revolution was for mass production) inspiration

comes from everywhere: the sky, the water, the moon, life—the

spirit of the moment. But that’s not true. A

flower’s not sentient. It doesn’t have a message that it’s

consciously trying to project to the universe. It’s just a flower,

existing, and doing what it’s supposed to do. More to the heart of

the issue is the perceptions of the artist, the viewer, the

listener—the feeler. They have to have their antennae up,

their blinders off … they have to be in a place where they can

receive inspiration, where, with whatever they’re feeling (these

emotions can be anywhere on the spectrum: joy, rage, jealously,

sadness), doing, observing, they’ve got to be vigilant for what can

be culled. Another way to look at it would be the cliché: Beauty’s

in the eye of the beholder. Well, so is inspiration. Most people

are familiar with the term intelligence quotient (I.Q.), and without

a doubt, being smart’s a plus. But for artists, and writers, in

particular, there has to be a healthy and active E.Q.—emotional

quotient.

My biggest hurdle has been in following

William Faulkner’s advice: “In writing, you must kill your

darlings.” See, when it comes to writing, revising, polishing,

refining, the artist has to be willing to murder, or cut something

they’ve gotten attached to when the piece/section doesn’t serve

the greater good. That’s a toughie, and yes, sometimes a

tear-producing event. In this, having great collaborators is a boon.

With Joel, others, sometimes they point something out that isn’t

working, and the water works get goin’, but what’s really

happening is the pulling out of a hammer and anvil, and then the heat

gets turned on; and what was fine before, valuable ore, becomes

something better—forged art!

Dave Hawkins: Rome wasn’t

built in a day, and neither are our songs. Joel brings in a part, a

fractal, if you will, then I do, or vice versa, then we work, chew,

gnaw on a piece till it’s shredded. We build a chunk up, then

reverse-engineer it back down. When we like something, we need to

know why. Identify what’s working, or … what exactly is keeping

something from bringing out the purity of the sound we’re shooting

for. It’s laborious, it’s wonderful. And when everyone in the

band and our passel of groupies has put in their 4.5-cents’ worth,

and we’ve landed a winner—it’s a high like no other. I’m a

grown man, a mature man, but with music, with my passion, I’m still

like a little boy, enamored with the beauty of it, the process, and

though I’m good at what I know, the end-product is often of such

quality, I’m humbled when I think that I had a hand in it.

With the creative process, a person

needs to recognize that there’s two halves to the brain, the logic

side and the feeling side (how’s that for simplification)—and

both are needed! Not just one. There’s times when the process is

work, workworkwork, and logic’s needed. After all, there are

notes, and certain notes produce certain constant sounds, arranging

such-and-such together will a-l-w-a-y-s produce a given effect. But

then—like with sports and other endeavors—there is getting into

the ZONE. And when that happens, when a person’s writing, playing,

whatever, they have to be willing to ride with it. And they’ll

need band members to let them—to trust them. Marrying the two’s

important, that right and left side process. Revision, rewrites,

tinkering, all that, is NOT a rebuke of the imaginative right side,

but rather an exercise of one’s mechanical imagination. In short:

When needed, workworkwork, when not, play and let the magic

happen.

Robert: The most important part

of the process is starting with the music first, and adding the

vocals at the end. This can be aggravating for our vocalists,

especially during the times when the lyrics are going through the

revision process, but it’s a necessary hassle. It’s the rare

duck that anything’s ever produced (of value) without blood, sweat,

and tears—and that’s okay. I enjoy the labored, and beautiful,

and organized chaos that precedes the final ‘baby.’ Growth is

birthed from work. One of the benefits to the way we work, is that,

indeed, we all get to work. Nobody skates, nobody rests on

their laurels—and better, no one’s ignored. Everyone’s got

their heartprint stamped on the music.

For those not familiar with your

work, how would you describe your music, and what are your

influences?

Joel: We’re a crossover prog

band, experimental to a point, with roots grounded in classical.

Influences are tough to pin down because they run the gambit, Yes,

K.C. (King Crimson), Floyd. What we don’t want is to be ripping

off any modern prog. With the old stuff, we lift away, and why not?

Mozart’s been dead for 220-years.

Kris: Our music’s so eclectic,

I think of it as a new genre: Progressive Plaid. With plaid, you’ve

got horizontal and vertical lines, many patterns, colors. That’s

us: Fractal Rock. There’s patterns in our music (that’s what

music is, patterned sound), but not the same pattern, over and over

and over and over and over again—that’s progressive-sh*t.

Dave Hawkins: Different. That’s

us. Hard to peg, dynamic sound. With music, there’s always a

certain amount of similarity because you’re dealing with

more-or-less standardized instruments and the human voice, and to

varying degrees, music can, and does, carry signature sounds, in

terms of genre/style/influence … but with, say, Kris and Deena’s

vocals and lyrical content, their work is anything but the same ol’

same ol’ derivative bullsh*t, was like nothing I’d heard in quite

some time, and with the work on our album, thing went, musically,

right where I wanna live—on the brink of insanity.

Robert: Not an easy question …

depends on the song. The knee-jerk answer, of course, would be

classical and rock (not to be confused with classic rock), and

certainly groups such as King Crimson, Yes, and other ’70’s

prog bands. The thing is, our goal, and something I believe

we’re succeeding at, is to put out music that’ll be timeless, and

continually relevant.

You’ve released Fractals

And Filigree as a free download through Jamendo, as well

as your own Web site. Why release a whole album? Was it just to get

the word out and perhaps score some gigs?

Joel: Fractals And Filigree’s

available from a number of sources: MadeLoud, Grooveshark,

SoundClick, and, of course, BitTorrent. And no … wasn’t for the

gigs. Instead, we wanted to groove our music to as many ears as

possible, as fast as possible. And we have. To date, F & F’s

been downloaded more than 35,000 times.

With playing live, we’re going wait

till we’ve got between 40-60 songs that can be done outside the

studio. Our timetable’s running to about three years before we’re

going to be ready. And why? The complexity, and that with both the

music, and the gear itself. It takes days in the studio just to

stage the gear and mics, and sometimes that’s just for say … the

drums alone. Synchronizing that kind of attention to detail for a

live-venue’s an awesome pursuit, but it’s also one we’re going

to be well-prepared for. Let’s just say, when we pull back the

curtain, we’re not going to f**k it up.

Kris: For those out there

working their music full-time, God bless ’em, that’s wonderful.

With us, money’s icing on the cake. For now, the big thing’s the

joy of sharing the music.

Dave Hawkins: There’s a beauty

to studio work that’s different from the stage. With the former,

we’ve produced a work of art! With the latter, our fans can know

that when they hear of us ready to headline, we’re going to be

doing the same—but in their face!

Robert: Some might argue about

the wisdom of giving out 17-songs. After all, that’s

representative of a lot time and work. But right now, exposure’s

key. People need to find out we exist, and just what it is they can

hear. With the digital resources available, for artists, it’s:

Adapt or or die. Plus, with the Net, we’re able to track

our music, focus the marketing, interact with our fans, the whole

sha-bang!—and on a global level. Really, for musicians, there’s

never been a better time throughout human history than right now.

When the day comes for us playing live, our audience can expect at

least a two-hour show of some fine-ass musical mayhem.

What’s on your table for next

year?

Joel: Write, record, and play.

Kris: Make more music … put

out another album.

Robert: Grow, baby. Grow and

grow. Our playlist, our skill-sets, our enjoyment of the craft, our

fanbase, all of it.

Any closing thoughts?

Joel: Just want to lay down the

challenge to everyone out there who digs prog. Check out our music.

Download it for free. If you love it, pass the word, friend us on

Facebook, and, by all means, drop us a line, commenting on our site

(http://fractalroack.pigboatrecording.com),

or sending us an e-mail. We do our best to answer all

correspondence.

Kris: For me, it’s been about

having a good time, and then having something to show for it—a

finished product. Fractal Rock’s opened up an entirely new world

for me, and I want as many others as possible to join in and be a

part of the ride.

Robert: Just want to thank

ProgArchives for the interview, and for all they do for the bands and

fans out there. For me, these past few years has been a blast, and

all I can say is, as much as the people have Fractals And Filigree

to love, wait’ll they see us live! Thank you to Fractal Rock for this interview |

|

|

|

The Neck Romancer

Forum Senior Member

Joined: June 01 2010 Location: Brazil Status: Offline Points: 10183 |

Posted: January 08 2011 at 12:21 Posted: January 08 2011 at 12:21 |

|

Downloading the album right now.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Post Reply

|

|

| Forum Jump | Forum Permissions  You cannot post new topics in this forum You cannot reply to topics in this forum You cannot delete your posts in this forum You cannot edit your posts in this forum You cannot create polls in this forum You cannot vote in polls in this forum |